Vettius Valens was a Roman astrologer who was conceived on May 13, 119 CE, and born on February 8, 120 in the city of Antioch, which is now modern day Antakya, Turkey. Today Valens is known for his encyclopedic 9 book astrological textbook the Anthology (Ἀνθολογίαι).

Vettius Valens was a Roman astrologer who was conceived on May 13, 119 CE, and born on February 8, 120 in the city of Antioch, which is now modern day Antakya, Turkey. Today Valens is known for his encyclopedic 9 book astrological textbook the Anthology (Ἀνθολογίαι).

Although he was originally from Antioch, at one point in his life he went traveling to Egypt in search of astrological doctrines that could be used in his practice.[1] After much trouble he found what he was looking for and subsequently settled in Alexandria and set up a practice and a school there.

The Anthology appears to be intended for Valens’ students, and seems to be dedicated to one of his personal students, relatives or friends in particular named Marcus.[2] Valens tells us that he wrote the Anthology as an “introduction” (εἴσοδος) for his students, although at one point he laments the fact that he could not make his writings more clear due to issues that he was having with his eyesight, as well as the emotional turmoil of losing his favorite student. (Bk. 3, ch. 13: 16)

The Anthology builds upon itself sequentially by starting off with the basic elements and techniques of horoscopic astrology such as planets and houses and then it gradually gets more complicated and technical as the work progresses and Valens explains how to use the various time-lord techniques.

The work itself was apparently meant to be kept secret, or was a part of some sort of mystery tradition, and Valens asks the reader several times throughout the Anthology to take an oath “to keep these things secret, and not to impart them to the unlearned or the uninitiated.”[3] These adjurations are typically concluded with what is essentially a curse to those who forswear the oath. Similar oaths are given in the work of the 4th century astrologer Firmicus Maternus.

Valens’s philosophical and religious sentiment is thoroughly Stoic, and he often embarks on a number of philosophical and moral asides throughout the course of the Anthology , some of which come off as quite poetic:

But those occupied with the prognostication of the future and the truth, by gaining a soul free and not enslaved, think slightly of fortune, and do not obstinately persist in hope, and do not fear death, but spend their lives without disturbance by training the soul ahead of time to be confident, and neither rejoice excessively in the case of good nor are depressed in the case of foul, and are content with what is present. And those who are not in love with the impossible carry along that which ordained, and being estranged from all pleasure or flattery, they are established as soldiers of fate.[4]

Editions and Translations of Valens’ Work

The original critical edition of Valens’ work was carried out by Guilelmus Kroll[5], with a later critical edition completed by David Pingree in 1986.[6] According to Pingree we owe the survival of a large portion of Valens’ Anthology to the noted 16th century English scholar John Dee, who compiled a massive collection of ancient and medieval texts at his library in Mortlake, England.[7] Dee apparently acquired his manuscript of Valens in 1556.[8]

Book 1 of Valens’ work was translated into French with commentary by Joelle-Frederique Bara.[9] Books 1 through 7 of the Anthology were translated into English by Robert Schmidt of Project Hindsight between 1994-2001 as preliminary translations, although final translations have yet to be published.

Valens’ Legacy In the Medieval Period

According to David King

Valens was known to the Arabs as Wālīs, sometimes with the appellation al-Rūmī, ‘the Byzantine’, which would correspond to his accepted provenance Antioch, but also sometimes al-Misṛī, ‘the Egyptian’, or, more specifically, al-Iskandarānī, ‘the Alexandrian’.[10]

Apparently he was also sometimes known as Wālintịyus.[11] A lost Pahlavī commentary known as the Vizīdhak (‘Anthology‘) was written in the 6th century by a Sassanian minister named Buzurgmihr.[12] This commentary was eventually translated into Arabic under a similar name (Kitāb al-Bizīdhaj), and although it influenced a number of Medieval Arabian astrologers this Arabic edition of Valens, like its Persian predecessor, is also lost. This Arabic translation of the Persian commentary on the Anthology is apparently how Valens work circulated throughout much of the medieval period.[13]

Valens apparently enjoyed quite a bit of fame with the Medieval Arabian astrologers. Pingree reports that there is a mid-10th century chart which supposedly reflects an interrogational question that was posed to Valens by the Persian king about the Islamic Prophet Muhammad.[14] Valens supposedly predicted great things about the Prophet based on the horary chart, so the Persian king threw Valens in jail, although eventually he was saved by God. Of course, the chart is a forgery that can be dated to November 7th, 939 CE, several centuries after Valens’ death, although Pingree points out that it does give us some idea as to the fame and notoriety that Valens had in the Medieval Arabian astrological tradition.

Elsewhere, Māshā’allāh lists 10 books of Valens that he is aware of, although it is not abundantly clear that he had access to the entire Anthology. [15]

In the later Latin tradition, after the 12th century translation movement, Valens was sometimes referred to as ‘Guellius’.

Other Articles on Valens

See my article on Vettius Valens on the Hellenistic Astrology Website for more in-depth coverage of Valens.

Endnotes

- 1. Vettius Valens, The Anthology , Book 4, trans. Robert Schmidt, Project Hindsight, 1996, pgs. 21-23.

- 2. Vettius Valens, The Antholog y, Book 7, trans. Schmidt, Project Hindsight, 2001, pg. 91.

- 3. Vettius Valens, The Antholog y, Book 7, trans. Schmidt, Project Hindsight, 2001, pg. 2.

- 4. Vettius Valens, The Anthology, Book 5, trans. Schmidt, Project Hindsight, 1997, pg. 21.

- 5. Guilelmus Kroll, Vettii Valentis Anthologiarum Libri, Berolini apud Weidmannos, 1908.

- 6. David Pingree, Vettii Valentis Anthologiarum Libri Novem, Lipsiae, 1986.

- 7. David Pingree, Classical and Byzantine Astrology in Sassanian Persia, pg. 228.

- 8. See Pingree’s critical edition of Valens, pg. x.

- 9. Joëlle-Frédérique Bara, Anthologies Livre I: Establissement, Traduction Et Commentaire, Brill Academic Publishers, 1989.

- 10. David A. King, ‘Some Arabic Copies of Vettius Valens’ Table for Finding the Length of Life’, in Symposium Graeco-Arabicum II, ed. Gerhard Endress, Amsterdam, 1989, pg. 26. A more expanded version of this paper was published more recently in a collection of papers dedicated to Pingree.

- 11. David King, A Hellenistic Astrological Table Deemed Worthy of Being Penned in Gold Ink, pg. 676 & 703.

- 12. David A. King, Some Arabic Copies of Vettius Valens’ Table for Finding the Length of Life, pg. 26.

- 13. Ibid.

- 14. David Pingree, Classical and Byzantine Astrology in Sassanian Persia, pg. 236. A Greek translation of this story, presumably from Arabic, is contained in CCAG 5, part 3, pg. 110. There is currently no English translation of it as far as I am aware, although Mark Reiley discusses it briefly in his paper A Survey of Vettius Valens, pg. 21.

- 15. This statement from Māshā’allāh is taken from a Greek translation of the original Arabic text which appears in CCAG 1, pg. 82. Questions about the accuracy of the list are naturally raised by the fact that it also lists Plato and Aristotle as having written books on natal and interrogational astrology as well.

5 replies on “Vettius Valens”

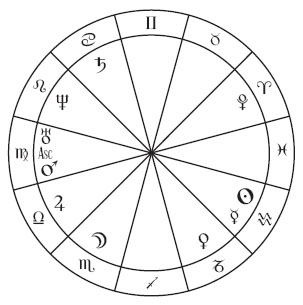

Are you using a sidereal zodiac for his chart here? How come. Did he use those positions?

This one’s interesting in tropical with the mutual reception of Merc and Saturn in the 5th and 10th whole signs.

Btw, it’s cool to see a chart where switching to sidereal (I’m using Lahiri) moves the planets forward. I’m not used to that.

Btw, he has kind of a strange chart; not one that I would’ve thought would be such a pivotal figure. I’ve seen a lot of powerful metaphysicians or astrologers with Mercury-Ketu though. I would have to guess that this the birth time he used for himself?

I reproduced the chart as Valens had it in the Anthology. He put Mercury in Aquarius, although, as you noticed, it switches to Capricorn using the tropical zodiac.

I found it interesting to see the sidereal zodiac move the planets forward as well.

We are under the assumption that this is his chart, and it was identified as such by Pingree, the critical editor of the Anthology. I don’t think that there are any explicit statements where Valens actually says it is his though. At one point he does seem to say that he may have had to rectify his chart because the time that his parents recorded was faulty or something.

Would you place a link to this Valen’s wiki here ?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vettius_Valens

-Is it possible to download free pdf’s of such Anthology?

I’m Pisces and one love shy of an ‘all spark.’ On the side of my college rigor, there are a pile of green lion alchemy books which tell of not spilling thy seed…..If such a topic was a bullet point, are there other bullet points you’re willing to bestow upon this not so uninitiated.

shd191@gmail.com

I think that you can order reprints of Schmidt’s translation of Valens through the Project Hindsight website. I would recommend doing that.